Lyons Explains Vernacular Art in The Conversation

What is vernacular art? A visual artist explains

Vernacular art is a genre of visual art made by artists who are usually self-taught. They tend to work outside of art academies and commercial galleries, which have traditionally been the purview of white, affluent artists and collectors.

In the U.S., vernacular art – which can also be called folk art or outsider art – is dominated by the works of African American, Appalachian and working-class people. In many cases these artists took up making paintings, sculptures, quilts or textiles outside of a day job, or later in life.

In early 2023, Christie’s held an auction of outsider and vernacular art. Featuring work by American artists such as Henry Darger, Bill Traylor, Thornton Dial, Nellie Mae Rowe, Minnie Evans and Joseph Yoakum, the sale grossed more than US$2 million.

Awareness and recognition of this genre has grown over the past few decades, with the Smithsonian Museum of American Art in Washington, D.C.; the American Visionary Art Museum in Baltimore; Atlanta’s High Museum; and the Milwaukee Art Museum building significant collections.

Art history as artist history

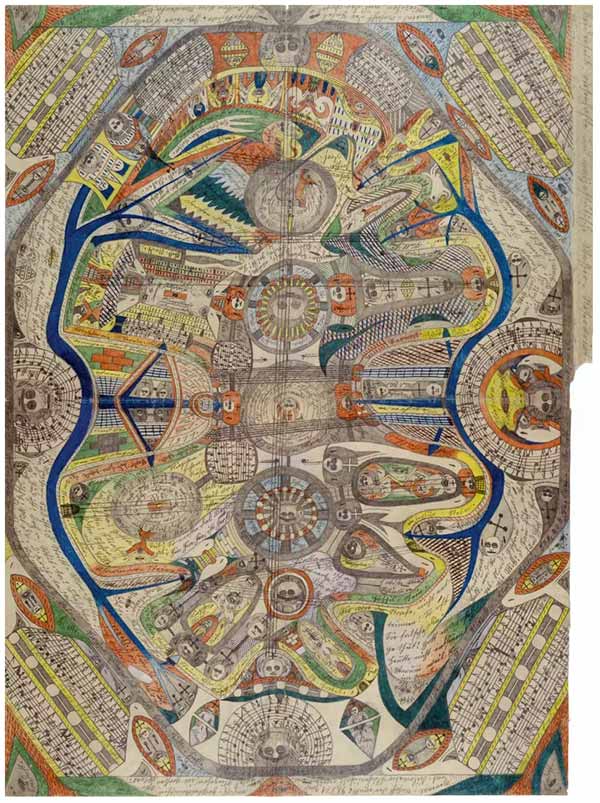

In the 1940s, the French artist Jean Dubuffet came up with the term “art brut,” which translates as “raw art,” to describe art made by mental patients, prisoners or children. The drawings of Adolf Wölfli, who died in 1930, inspired Dubuffet’s term.

Wölfli was a patient with schizophrenia in a mental hospital in Bern, Switzerland, who was given pencils and paper as a form of therapy. Working mostly in pencil, Wölfli created elaborate drawings with decorative borders that included symbols, letters and his own system of musical notation.

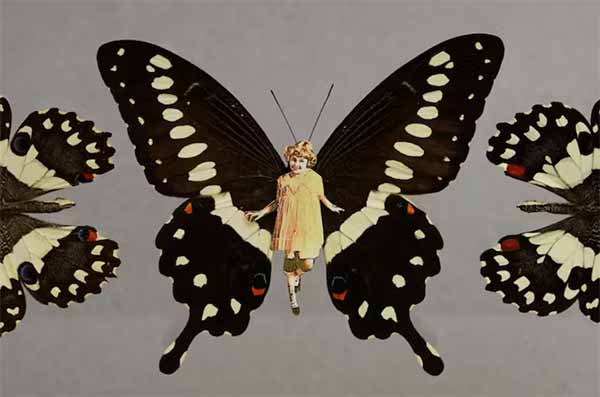

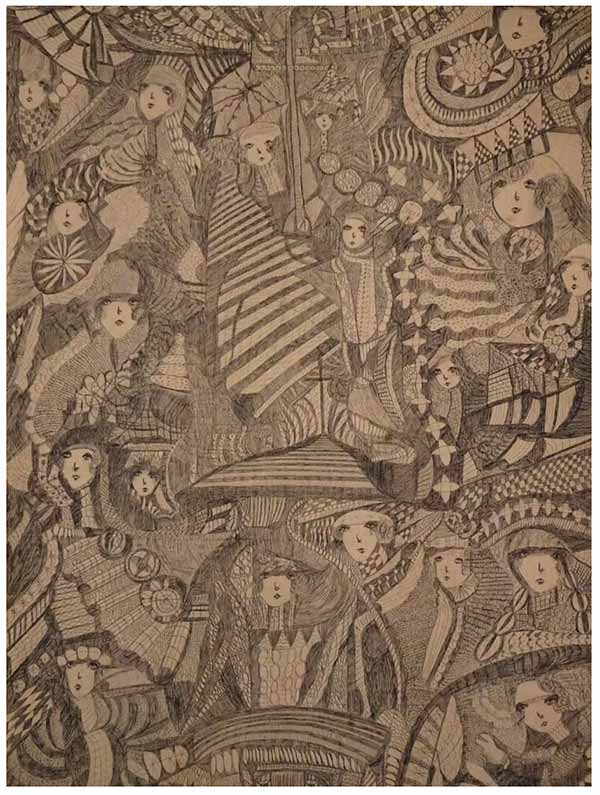

In an effort to promote this genre, in 1972 the British art historian Roger Cardinal advanced the term “outsider art” to expand the canon and include more artists, such as Madge Gill, who died in 1961. Gill, a British self-taught artist who spent much of her childhood in an orphanage, started making highly patterned drawings at the age of 38, claiming to compose the works while communicating with spirits.

In his 2004 book “Everyday Genius: Self-Taught Art and Culture of Authenticity,” sociologist Gary Allen Fine explains that a common facet of vernacular art is an emphasis on the artist’s biography: their personal, family and employment history. Fine observed that to collectors and dealers, these stories seemed to imbue the art with more meaning – and value. Some curators have argued that vernacular art should be included in exhibitions of contemporary art and not merely exist in its own siloed category.

But the relationship between vernacular artists and their promoters can be complicated.

In her 1998 book “The Temptation: Edgar Tolson and the Genesis of Twentieth-Century Folk Art,” sociologist Julia Ardery explored the ways that Tolson, a self-taught woodcarver from rural Kentucky, interacted with faculty and students from the University of Kentucky, and she analyzed their influence on his art.

Much of Tolson’s work was acquired by Michael Hall, who taught at the University of Kentucky at the time. Hall helped Tolson receive a National Endowment for the Arts Individual Artist Fellowship in 1981, but he also ended up selling a portion of his collection to the Milwaukee Art Museum in 1989 for $1.5 million.

As the sale of Tolson’s work shows, when huge sums of money enter the picture, the line between appreciation and exploitation gets blurred.

Why vernacular art matters

Vernacular art extends the artistic canon in the same way that folk music reflects broader traditions of expression. It reminds everyone that art is a universal human pursuit.

As the late Chris Strachwitz, the founder of Arhoulie Records, has pointed out, Black traditions of blues and roots music were not formally taught but were passed down from one generation to the next in local communities.

Similarly, the architect Robert Venturi promoted vernacular architecture in his 1972 book “Learning from Las Vegas.” In it, he highlighted the ways that Las Vegas casinos and hotels were designed to accommodate the automobile and were meant to be seen as symbols, with massive, outlandish signs – an approach that most schools of architecture would have scoffed at. In doing so, Venturi ushered in more playful forms of architecture.

Concepts of authenticity are central to the appeal of vernacular art. Fine art and culture can sometimes be esoteric and exclusionary, and in a time when artificial intelligence has put authorship in question, vernacular art has even more resonance. It is made by the artists’ hands, using common materials, in ways that reflect their own unique life and artistic visions.

This work represents a pre-digital form of expression, accessible to anyone, that showcases what it means to be resourceful, creative and human.

—Beauvais Lyons, Chancellor’s Professor of Art, University of Tennessee

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.